One of the most remarkable episodes in the history of the use of tobacco in the Netherlands is no doubt the period when the entire tobacco-trade and manufacturing was declared a state-monopoly by order of Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte. The story goes that at a ball Napoleon saw a lady who wore the most magnificent and expensive jewels. He asked who she was and it turned out to be that she was the wife of a tobacco-merchant. The emperor exclaimed in amazement: “What a lot of money that man must earn!” This reaction is said to have resulted in the imperial decree of 29 December 1810, which introduced the tobacco-monopoly in France. This led to the decree of 26 December 1811 which introduced and finally settled the state-monopoly of tobacco in the Netherlands.

The tobacco-trade, which provided a livelihood for hundreds of merchants, workmen, and shopkeepers, and was among the few sources of income that were left, reverted to the Emperor. He made his people buy up all the tobacco and afterwards sold it again for 5 times the price he paid! In this way the “big tobacco-dealer” gained huge amounts of money, which he could well use to carry out his warlike plans. These few lines practically tell the whole story of the Dutch state-monopoly. But many details of the organization of this are so interesting that they are certainly worth telling about.

Napoleon’s tobacco policy was all-embracing. This is clearly illustrated by the first part of the above-mentioned decree of 26 December 1811: “Only the Board of the United Rights is entitled to buy tobacco-leaves. Anybody who is not a planter, is forbidden to have tobacco-leaves in his house. Tobacco-leaves may not circulate without a waybill. Anybody who wants to grow tobacco is obliged to give notice of this to the burgomaster of his municipality before the 1st of March of every year, stating where the piece of land he wants to plant, is situated, its size, the number of plants he wants to grow there, and the space he intends to leave between the plants.” Further the minimum size of an area to be planted with tobacco was fixed at 4000 m2, while the price was to be announced every January. With the above mentioned waybill, the tobacco was to be taken to the appointed warehouses where cash money was paid for it. Keeping back any tobacco was most severely punished, namely by expulsion. High demands were also made upon the delivery of the tobacco. It had to be tied in neat bunches and was not to contain any buds or stalks.

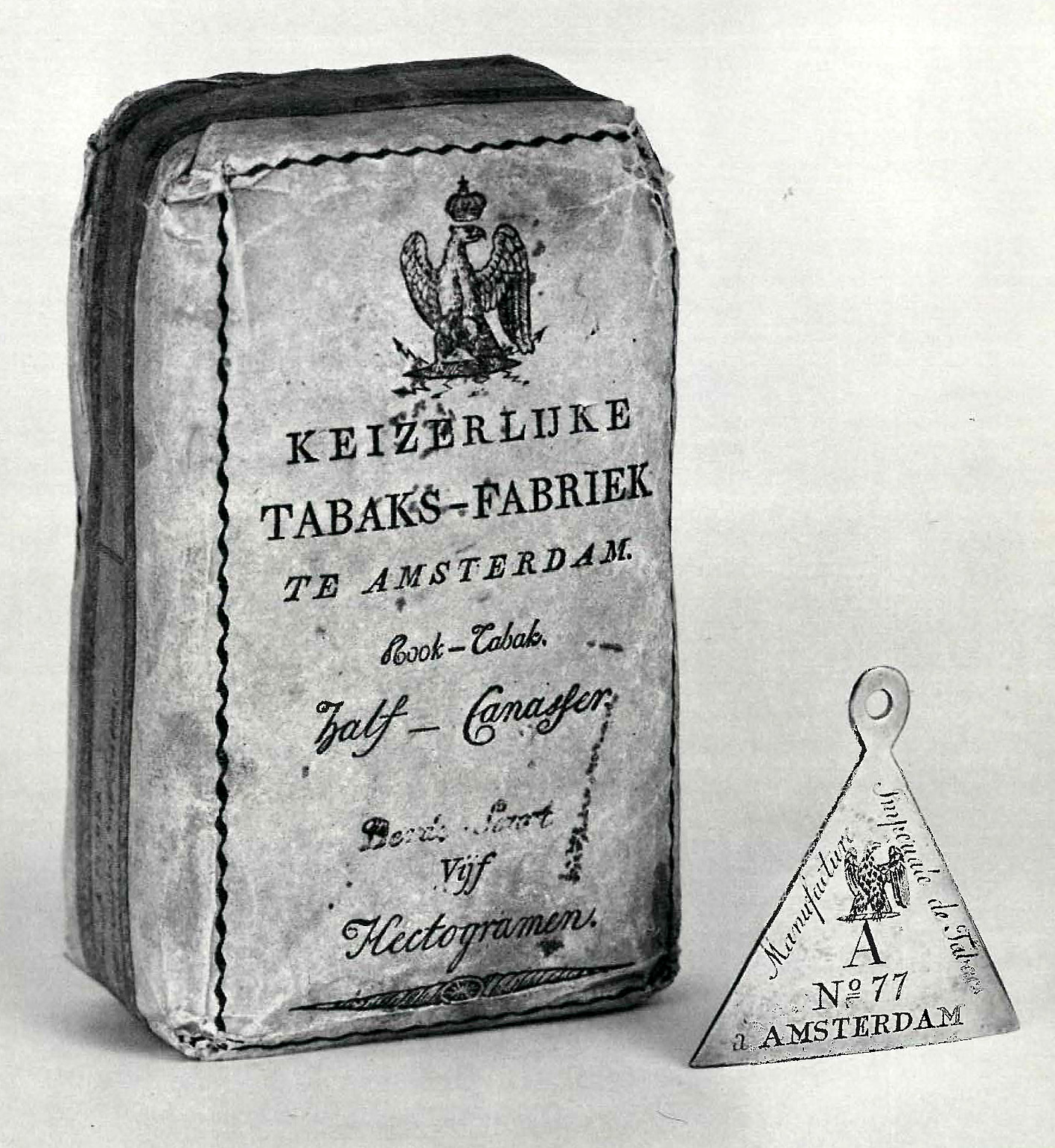

Of course the retail trade was no less strictly organized: “Nobody shall store any other kind of manufactured tobacco but that which comes from the imperial factories. It is forbidden to store any other kind of tobacco. Only those who have been granted a licence by the Board may sell manufactured tobacco. They are not allowed to lay in any stock, except from the Board’s warehouses, situated in their district. Nor are they allowed to have in the house, any tools such as rasps, mills, cutting-frames, sieves or any other instruments whatsoever for the preparation of tobacco.” The already present stock was not forgotten and had also been taken care of: “From the 1st of November 1811 all planters, dealers, manufacturers, merchants, tobacconists and other sellers of tobacco will be obliged to inform the Officials of the United Rights of the quantity, origin and quality of the tobacco-leaves they possess. These will be inventoried, sealed, bought by the Board, and paid for in cash money on the central pay-office at…..”

On the 1st of January 1812 the tobacco-sellers, to whom a licence had been granted, had to start selling. As appears from the instructions of the inspector of the United Rights, dated 24 December 1811: “Those sellers of tobacco who continue in office from the 1st of January are being notified that delivery of the tobacco, manufactured in the special storehouses of the Board, is to take place on the 29th, 30th, and 31st of the current month of December. Consequently, every seller is obliged to go there in order to receive the quantities, qualities and brands he thinks he will need. He must have his security-receipt with him.” On the 31 December 1811 further rules were published with which the retailers had to comply. “The sellers will not be allowed to lay in any stock of quantities under ten kilogrammes. They will have to have a way-bill. In the hands of the keeper of the private warehouse, they are to pay cash the price of the tobacco, as regulated by the decree of 22nd October last, except for the discount which shall be mentioned hereafter. They may not sell any tobacco at higher prices than those fixed for the sellers, nor may they sell inferior tobacco at the price of better quality tobacco on penalty of being prosecuted, having been found guilty of extortion. The discount, which, in accordance with section 57 of the decree of 12 January 1811, shall have to be granted to the sellers for short weight, has been fixed at 5 per 1oo. This will be deducted from the amount of tobacco which the sellers are to collect.”

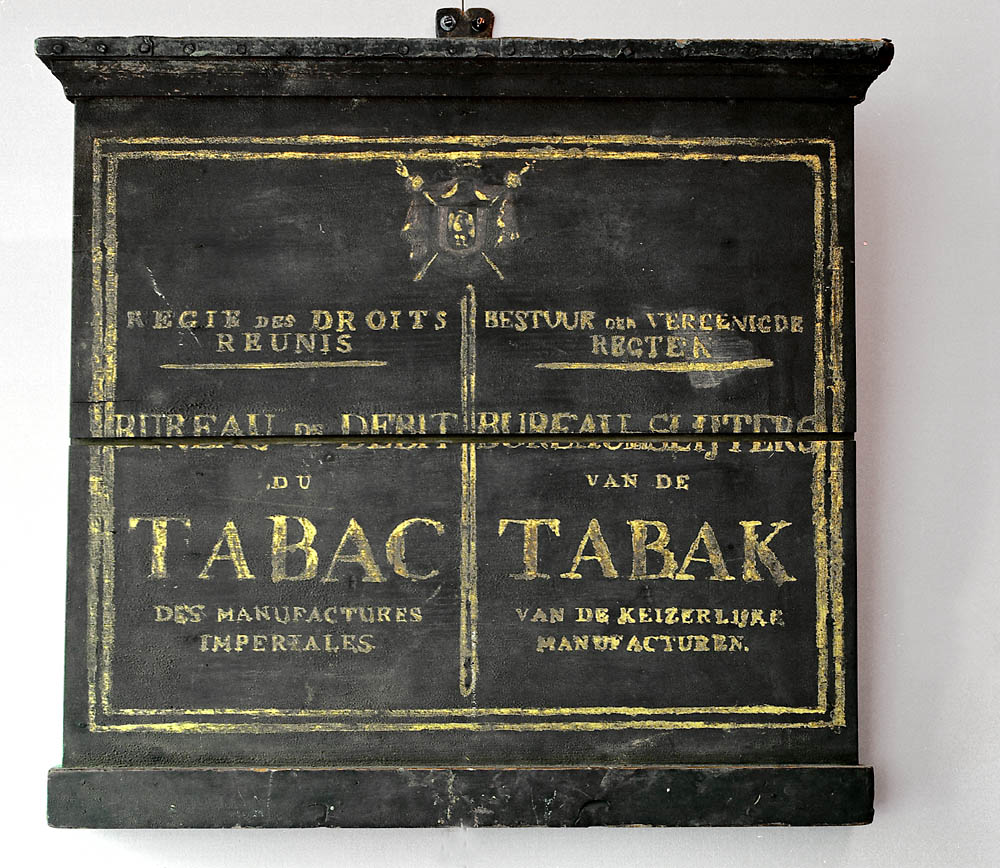

“They will have to offer their tobacco for sale in jars, bearing names, showing from what factory the tobacco came, its brand and its price. They shall be obliged to arrange the above-mentioned tobacco in their offices or shops according to the factories, brands and prices, in order to facilitate the verification by officers. In the place where the tobacco is being sold, they are to hang a list of the brands they sell, and outside the store they are to place a signboard. They will only be allowed to break the lead seal of the bags or casks of tobacco to be sent to then in the presence of officials of the Board who shall be called in to sign the waybill. If, however, there are no officials living in that place the seller will be allowed to break the lead seal. He may, however, always be required to show it. The sellers are free to unpack the tobacco and to pour it from one jar into another at will. But they will not be allowed to mix any tobacco. Not even the first quality tobacco of one factory with first quality tobacco of another. They will have to arrange the tobacco in their shops according to brands and grades and on every cask or other vessel they shall stick a label, indicating the factory where the tobacco was manufactured and its brand and grade. On no account are the sellers allowed to moisten the tobacco. The sellers will be obliged to provide themselves with scales and metrical weights, properly stamped and verified. With these weights they will not be allowed to make a combination equalling the old pound weight. They will keep accounts of what they sell, according to a system to be issued to them. It will be submitted to the verifications of the tobacco-officials.” And verify they did. There are records that the officials verified the books of a tobacconist in Haarlem 59 times in the period of almost a year.

By the middle of November 1813 the Netherlands were in an uproar. The French officials and their Dutch confederates were packing up and fled their posts hastily. Everywhere the hateful signs of the “Régie des Droits réunis”, with the imperial eagle, were torn from the tobacco-shops and trampled upon. Only a few were left and ended up in our museums. Enormous quantities of régie tobacco fell a welcome prey to the Russian liberators, who did not prove to be too picky.. There must have been huge supplies of tobacco. In the city of Groningen the Russians found as much as 76.000 kg stored in two depots. Everywhere retailers got stuck with large stocks. For only few people wanted to buy the régie products when superior tobacco from overseas began to pour into the country once more. Probably the remaining state-monopoly tobacco was bought by the poor people of those days at reduced prices, or maybe it was used by the bee-keepers to smoke out the bees. Who knows?