Adieu, vaarwel, goodbye café De Waagschaal… For years your smoking room was the last refuge for the smoker in the region I live in. Myself and other pipe smokers had so many great and cosy meetings there over the years. Also I just liked to sit there alone with a good cigar/pipe, read a book, have a cup of coffee and look at the people outside walking over De Brink (the central square in Deventer). Now a (grumpy) owner closed it down due to recent regulations, although those are not enforced until April 2020. I was hoping for one last warm winter of smoking but unfortunately there is a small club of anti-smoking people here (Clean Air Nederland) who sued the Dutch state about their smoking room policy, and won… Unbelievable… I fetched my own drinks in the café below and carried them to the old smoking room, personnel did not even had to come there, and I bothered no one. Civilisation, don’t make me laugh… Luckily I still have the pictures, thanks to all who took them.

Tag Archives: deventer

The tale of the “Diepenveensche Tabak Centrale”

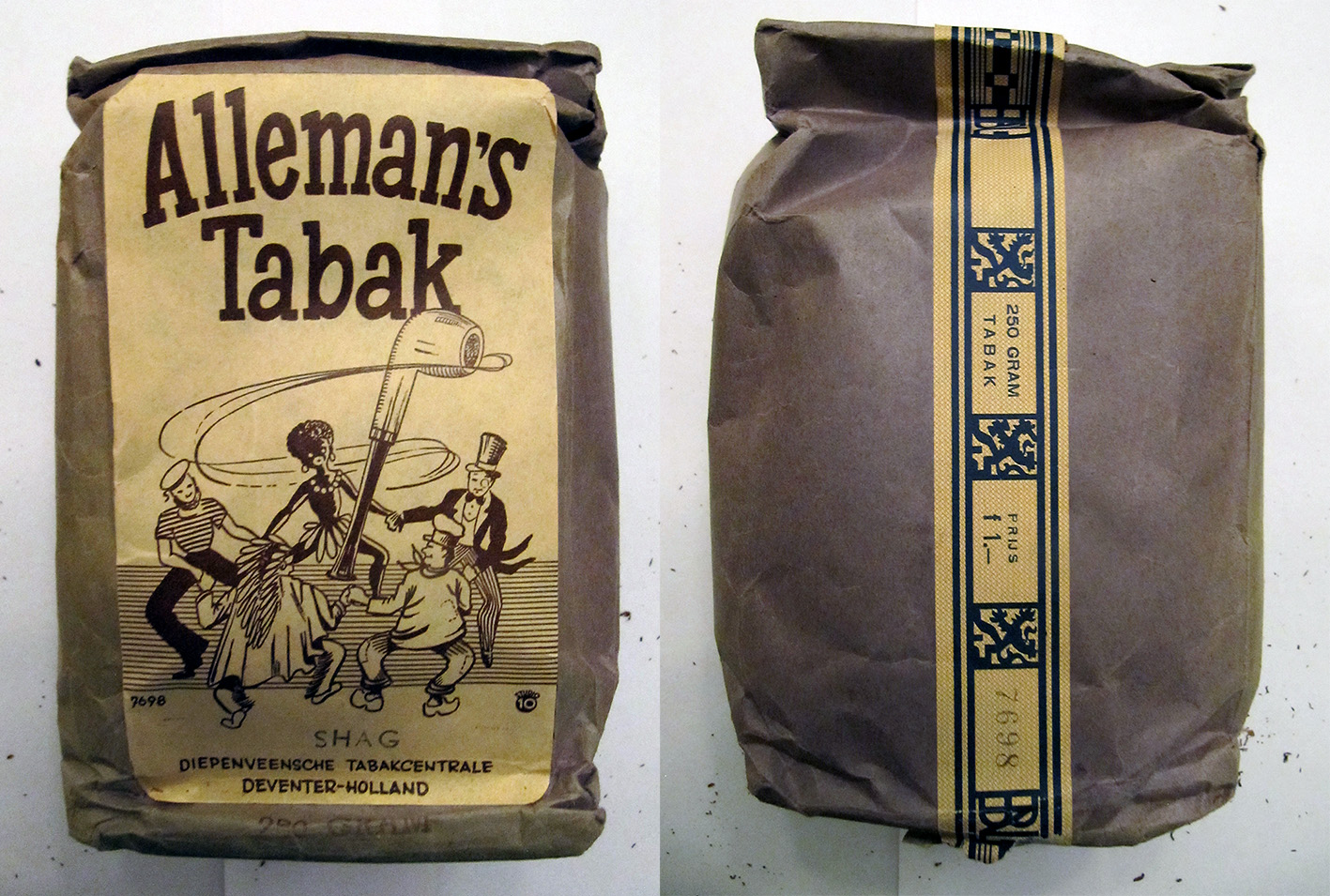

This story began a couple of years ago when Martin gave me an old looking pack of tobacco at one of the Zutphen meetings. He had it in his possession for a long time but figured it was in better hands with me. The name on the pack was “Alleman’s Tabak” (Every man’s tobacco) with a nice looking picture on it of people from all races dancing around a smoking pipe. But what mostly caught my eye was where it was made: The Diepenveensche Tabak Centrale (Diepenveen Tobacco Centre) in Deventer. Hmmm, Deventer is the nearest city to Olst, where I live (about 10 km. away) and the village of Diepenveen lies in between those. Ellen and I sometimes cycle to Diepenveen in summertime because of the beautiful nature along the way. At home I began to search for the Diepenveensche Tabak Centrale (DTC) on internet and soon stumbled upon a small book about the subject written by Jan Jansen (a former tobacconist) and Ben Droste. It was already out of print but I managed to snatch up a copy (thanks to PRF member Carro) at De Oude Leeuw tobacconist. So here is the tale of the Diepenveensche Tabak Centrale.

When the Netherlands were invaded by the Germans in May 1940 it soon became clear that many ships loaded with foreign tobacco were not going to make it to our harbours. It was estimated that the current stock at the time would last for 3 years. This was thanks to the cigar-industry which kept a multiple-year supply in order to be able to blend a good melange in years of a disappointing harvest. So there was enough smoking leaf stocked in the warehouses and everyone assumed we were going to keep that supply. That we would be stuck 3 years or more with our undesirable Eastern neighbours seemed like a ridiculous idea at the time. But before the Germans occupied our small country they were one of the biggest buyers of our cigars and other tobacco products. In other words, they knew what we had and with haste they registered our tobacco stock and transferred 60% of it to Germany. Then it was estimated that the Dutch tobacco industry had supplies to keep producing until the middle of 1941… Whoops…

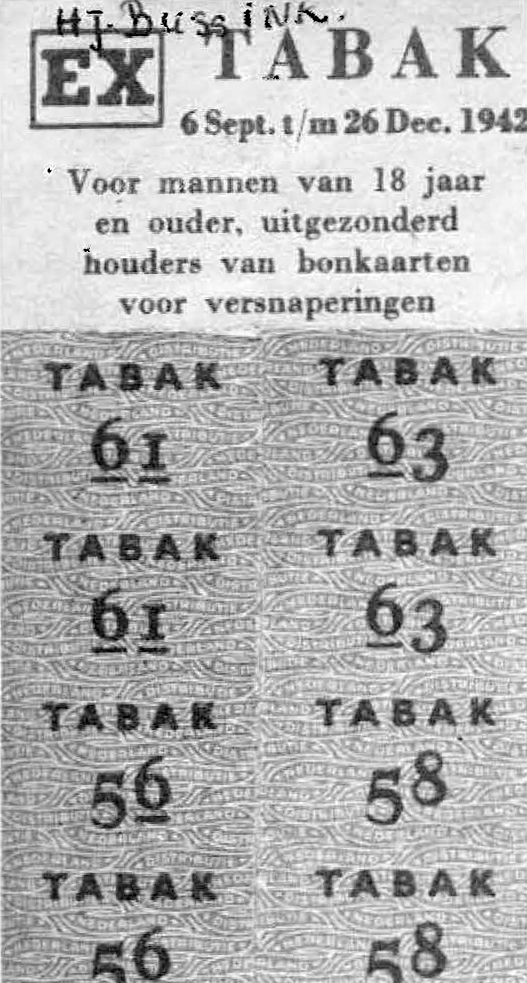

Spring 1942. The war was raging for almost 2 years and even the most desperate smoker understood that the ships loaded with tobacco, coming for example from our former colony of Indonesia, were not arriving. However, tobacco products were not rationed yet but especially foreign brands were terribly expensive due to scarcity. For the common man rationing did not seem too bad, at least everything would be divided equally then. And indeed, on 17 May 1942 tobacco and candy were rationed. First every man got 50 gram per week (women got less…) but in 1943 that was reduced to a mere 20 grams.

At the end of the first war-year it was reported in the press that in that year about 22 hectares of tobacco were grown, almost half of it by private citizens. Many amateurs had risen. They had seen the coming storm and bought some seeds or plants. They were not nine-day wonders, they plodded on with this tricky crop and gained more and more followers. Soon the government informed the amateur tobacco growers that they could get their harvest fermented and cut at Rijksbureau voor Tabak en Tabaksproducten (National Bureau of Tobacco and Tobacco Products) recognized companies. Upon delivery to the customer excise duty and sales tax had to be paid. The companies could not ask more than fixed prices. Especially the very important fermentation of the tobacco leaves was difficult for the amateur grower. Growing the tobacco-plant, harvesting the leaves and drying them was doable with a proper instruction. But it was not for nothing that the government forbade the amateur grower to ferment his own tobacco. That was a job for a professional and it was a shame to waste valuable ground to tobacco that had gone bad due to a clumsy fermentation process.

The founders of the DTC choose a good moment to launch their plan. After 2 years of war the need was great with the smokers. The main founder was horticulturist Keurhorst. He was not just any horticulturist, his letters were crooked but he could read and write with plants and flowers which earned him many prizes and certificates. Without doubt he examined the experiences of growing tobacco on Dutch soil very thoroughly when he saw opportunities in the tobacco-market at the break-out of war. There was money to be made with being a Rijksbureau voor Tabak en Tabaksproducten recognized company. He also wanted to grow tobacco plants and process those into chewing and pipe tobacco, cigarettes and cigars but realized he lacked the knowledge for this. So he approached a man called Weverling. Weverling was destined by his parents to be a teacher but he “escaped” to Indonesia. After a few jobs, while travelling through the islands, he ended up managing work at tobacco plantations. in 1936 he returned to The Netherlands and went to live in Diepenveen where he first met his wife. It was easy to get Weverling excited for Keurhorst his plan. After his return he wanted to live from the trade in (mostly Indonesian) stocks but due to the war that went pretty wrong. Besides, Weverling was not a man who liked to do nothing and this brought him some work. The most important task assigned to him was the fermentation of the tobacco.

The third and final founder was Van Santen. His duty was to start up and manage the administration of the starting company, get all the permits etc. The aim of the German occupier to control all processes in our society led to a large and often untransparent bureaucracy. The rules were plentiful and meticulous. Keurhorst did not have to worry any more about the fermentation of the tobacco. However, cutting it.. For that he choose a company in Deventer with a long history: Harm’s ten Harmsen with Van Nieuwland as director (together with his father), founded in 1758. From the start it was a”mixed” business. It traded in tobacco and tobacco products but it also processed the leaf into snuff and pipe tobacco and cigars.

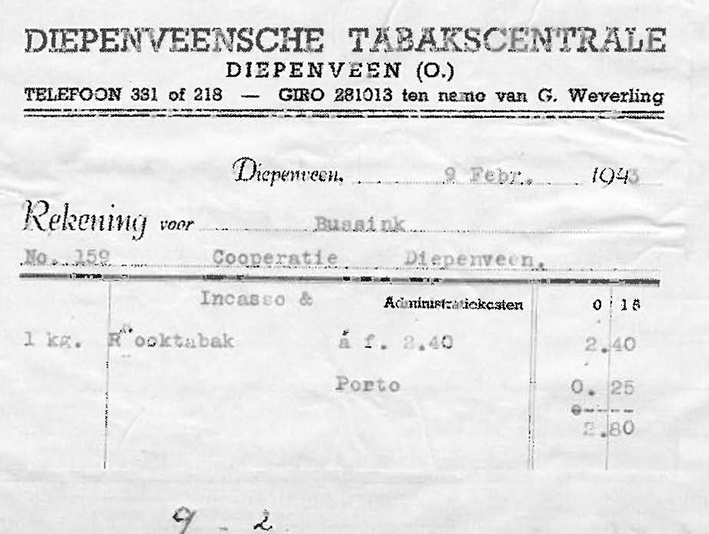

The 3 men must have done an enormous amount of work in their first year. In fact everything they did at the starting corporation was new for them. Besides the time pressure was huge. Everything had to be ready so customers could send in their home-grown tobacco to let it ferment and cut. They very wisely decided to limit them selves to the service to the amateur grower in stead of immediately trying to grow tobacco of their own. The tension must have been great. Do the permits come in time? How much tobacco is going to come in? Will the new company be able to deliver an acceptable product? Will the tropic experience of Weverling hold up in the Dutch climate? Will they be able to manage the complicated administration? Oh, about the administration, it turned out that Van Santen did not do a good job. So after a heated argument he left the company and Van Nieuwland took over his work. The whole administration was even moved to the address of Harm’s ten Harmsen.

On 16 March 1943 the Diepenveensche Tabak Centrale was registered at the Trade Register. Soon they encountered a problem; there were not not enough available free spaces for the drying and fermentation of the tobacco in Diepenveen (poor on industry). However, in Deventer stood the factory of Horst & Maas (where amongst others cigar brand Nederlandsche Munt was made) and because of the war activity here had become minimal. The DTC got 18.000 m3 available for their activities. The representative building also accommodated a large scale demonstration of the fermentation process for amateur growers on 7 November 1943.

So how did the exact process go when amateur growers wanted to send in their home-grown tobacco to be fermented and cut by the DTC?

1. You had to register at the DTC.

2. The costs of registering had to be paid.

3. You got a card from the DTC on which you had to write how much tobacco you were going to send.

4. You got a message from the DTC in which was asked if you wanted shag, pipe or chewing tobacco. Then you could send the tobacco.

5. After the fermentation and cutting the tobacco would be send home. Costs had to be paid upon receiving the package

Important to know was that it was not possible to get back the same tobacco one send in due to technical reasons. The melange would not be tasty with tobacco coming from just one package. Besides, fermenting and cutting very small batches of tobacco was not doable. Upon receiving a package the DTC checked the quality of it. So when someone send in an A-quality batch of tobacco he got an A-quality batch back.

It is clear that for all this work the DTC needed a lot of hands. But getting employees was a perilous undertaking in the war. Already in the first years of the war the Germans were recruiting workers in the occupied areas who had to take the places of the men in the German industry who had to fight in the front lines. In the beginning the appearance of voluntariness was upheld. The tactic then was: make them unemployed and offer them work elsewhere (read: Germany). They could not reasonably refuse that and if they did that was a good excuse to arrest them. To escape that employment in Germany a cat and mouse game went on in the tobacco sector in which the Centraal Distributie Kantoor (Central Distribution Office) and the Rijksbureau voor Tabak en Tabaksproducten often secretly sided with the mouse. They must have known that the fields with meters high tobacco plants were ideal hiding places for a couple of months per year for people who had to hide. In Diepenveen it was secretly known that persons in hiding worked at the DTC. Those people were called “volunteers” because you did not have to name volunteers in the administration books. So for an important part the company relied on “illegal” employees.

Sadly on 17 October 1944 father Van Nieuwland died because of a heart-attack. To make things worse his son got buried under the debris of his own company building during an allied bombing on 15 December of that same year. So in a short time the DTC lost their business partner and a large part of the administration. And then, suddenly, like a lifesaver, there was C.G. Bloemink. In more quiet times he had been a tobacco-broker but when the war held up the trade he hired out himself as a civil servant and ended up in Deventer. At the end of 1944 he was an eye-witness when Harm’s ten Harmsen was bombed. One man’s misfortune is another man’s opportunity, this was the chance for Bloemink to work in the tobacco business again. On 17 January 1945 he was registered as a partner, got the title of managing director and became the face of the DTC. After the bombardment where Van Nieuwland died his mother passed on the company Harm’s ten Harmsen to one Frederik Koster. Bloemink took advantage of the opportunity to abruptly end the partnership and choose to work with the company Ten Have. The administration (what was left of it) moved to De Brink 32 in Deventer, beside his new partner.

On 24 June 1946 it was noted in the Trade Register that Weverling and Keurhorst had left the DTC on 1 March of that year and that a new partnership was founded with C.G. Bloemink as its sole owner. The exact reason for their departure is not known. During the liberation of Diepenveen the greenhouses of the DTC with new tobacco plants meant for further processing and sale were destroyed, which was a big setback. Or perhaps they saw the end coming of inland grown tobacco now the war was ended. Keurhorst stayed being a horticulturist and tried (successfully) to develop better tobacco seeds and plants. Weverling got an offer to set up a plantation in Java which he gladly took, he had always longed back to the tropics.

Bloemink must have fought like a lion to keep the business running. Probably against his better judgement, because he was not a stupid man and the end of inland grown tobacco was easy to predict. Whether he liked it or not, our Dutch tobacco would always be of inferior quality as opposed to what America, Indonesia and other countries had to offer. In 1950 the location at De Brink was left and Bloemink made his office at home. In 1959 the Trade Register mentions a new address and name: Tabakscentrale. With that the Diepenveensche Tabak Centrale became history. The adventure began near Deventer and found its end in the city itself.

So why did you not wrote this story several years ago you lazy bastard! One could think.. Well, because the book also mentioned there was a film made during the war called “Toeback” in which the DTC played a large role. This movie about the growing of tobacco was made by Deventer photographer and film producer Alex Roosdorp. The filming began as a hobby but soon it became a full-time job for him and his wife Marie. Together they travelled across the country recording nature for commercial and educational purposes. It should be no surprise that Roosdorp, who liked to explore the nature around Deventer on bike, stopped at the tobacco plantation of Keurhorst. Probably the idea to make a film there was born at that occasion. The educational movie shows the growing and processing of tobacco and was premièred in November 1943. Sadly after the war the film got lost and forgotten.

But when Jan Jansen was doing his research he stumbled upon the original tapes of Toeback. It turned out to be a silent movie but in colour! Very rare for that time. With money from the Nederlandse Vereniging van de Sigarenindustrie, the Vereniging Nederlandse Kerftabakindustrie and the Stichting Sigaretten Industrie the film was restored by the EYE Film Institute, put on DVD and given to the Stichting Nederlandse Tabaks Historie, run by Louis Bracco Gartner. Now and then the DVD was shown upon request but that was it. When I heard about the existence of Toeback I thought that it would be awesome if it was available for anyone to see. Because it is an unique document for the Netherlands and perhaps for the world. So after some searching I found out Louis had the film, but he could not just rip the DVD and put it on internet. He had to ask permission from the EYE Film Institute. That process almost took 2 years and a lot of e-mails from my side (and probably also from Louis) but lo and behold, a short while ago I got a message from a happy Louis with the link of the movie! The EYE Film Institute had finally uploaded it on YouTube. So sit back, pour yourself a glass a good whisky, put on some relaxing music, light up a pipe and enjoy Toeback.