My love for Dunhill pipes began when I purchased a Dunhill Bruyere pot model from 1976 through a member of the Dutch pipe smokers forum. Before that I had a couple of bent Petersons, a few Winslows and that was it. I was searching for a really good pipe to smoke latakia-blends in, a pipe that would do a fantastic blend justice. And well.. The Petersons did not cut it.. Absolutely beautiful pipes but as far as smoking goes.. Mwah.. I must say, I still have a Peterson from 1923 and that one smokes superb. But the newer ones were just not my thing. My Winslows are superb pipes for aromatic and Virginia/Virginia-Perique blends, but latakia, no. At first I saw a Dunhill pipe as a bit snobbish, not something I like. But when I read something more about the history of Alfred Dunhill (I love history) I began to feel more for the brand. The Dunhill Bruyere pot I bought was a great smoker when filled with the dark leaf. It just tasted better, the draft was better, the mouthpiece felt better etc. But I did not like the look of the pot very much. And then I fell in love with the Prince shape.

My love for Dunhill pipes began when I purchased a Dunhill Bruyere pot model from 1976 through a member of the Dutch pipe smokers forum. Before that I had a couple of bent Petersons, a few Winslows and that was it. I was searching for a really good pipe to smoke latakia-blends in, a pipe that would do a fantastic blend justice. And well.. The Petersons did not cut it.. Absolutely beautiful pipes but as far as smoking goes.. Mwah.. I must say, I still have a Peterson from 1923 and that one smokes superb. But the newer ones were just not my thing. My Winslows are superb pipes for aromatic and Virginia/Virginia-Perique blends, but latakia, no. At first I saw a Dunhill pipe as a bit snobbish, not something I like. But when I read something more about the history of Alfred Dunhill (I love history) I began to feel more for the brand. The Dunhill Bruyere pot I bought was a great smoker when filled with the dark leaf. It just tasted better, the draft was better, the mouthpiece felt better etc. But I did not like the look of the pot very much. And then I fell in love with the Prince shape.

Like I said in my “Prince of Pipes” post, for me the epitome of the prince pipe is an army mount Dunhill Shell briar from the patent era. Why a Shell? I guess just personal preference, I like a beautiful sandblast more than a straight grain. But how did the Dunhill Shell pipe came into being? The “marketing” tale is this: Alfred Dunhill went down into his basement during winter. He wanted to make a couple of pipes (as far as I know he was a gifted blender, not a carver, but ok..) and he accidentally left a half finished one by the heating boiler. Sometime next summer he suddenly thought of the pipe. He found it and it looked like some of the grain had “shrunk”, leaving a relief pattern similar to that of a sea-shell. In reality the company experimented since 1914 with Algerian briar (attractive and pretty inexpensive) for a smooth-finished pipe. But without success because of the softness of the briar. So the blocks were simply laid aside the stove. After several months it seemed that the heat from the stove had affected the condition of the Algerian briar blocks. They had shrunk to a mere “shell” with the grain standing out in relief similar to that of a sea-shell (I feel like repeating myself). And so the Shell finish was born. Working together with the London Sandblasting Company to perfect the process of accentuating the briar relief, a patent was finally awarded in late 1918.

Like I said in my “Prince of Pipes” post, for me the epitome of the prince pipe is an army mount Dunhill Shell briar from the patent era. Why a Shell? I guess just personal preference, I like a beautiful sandblast more than a straight grain. But how did the Dunhill Shell pipe came into being? The “marketing” tale is this: Alfred Dunhill went down into his basement during winter. He wanted to make a couple of pipes (as far as I know he was a gifted blender, not a carver, but ok..) and he accidentally left a half finished one by the heating boiler. Sometime next summer he suddenly thought of the pipe. He found it and it looked like some of the grain had “shrunk”, leaving a relief pattern similar to that of a sea-shell. In reality the company experimented since 1914 with Algerian briar (attractive and pretty inexpensive) for a smooth-finished pipe. But without success because of the softness of the briar. So the blocks were simply laid aside the stove. After several months it seemed that the heat from the stove had affected the condition of the Algerian briar blocks. They had shrunk to a mere “shell” with the grain standing out in relief similar to that of a sea-shell (I feel like repeating myself). And so the Shell finish was born. Working together with the London Sandblasting Company to perfect the process of accentuating the briar relief, a patent was finally awarded in late 1918.

Another invention was the treating of the wood with oil (oil curing), which strengthened it and removed impurities. Here is how Alfred Dunhill explained the process of oil curing and sandblasting in the patent application: This invention relates to the treatment of the surface of the wood of wooden tobacco pipes, for decorative purposes, and refers to a process by which the grain is accentuated or made to stand out in relief, thus giving the wood a very elegant appearance, without interfering with the durability of smoking qualities of the pipes. Although the sand blast has been used previously for the treatment of the surface of wood, to accentuate the grain, I have found in practice that this treatment in itself does not give satisfactory results as there is a tendency for the wood to become cracked and injured, a result that does not occur with my process where it is used as an auxiliary to the treatment by steeping (in oil) and by heat.

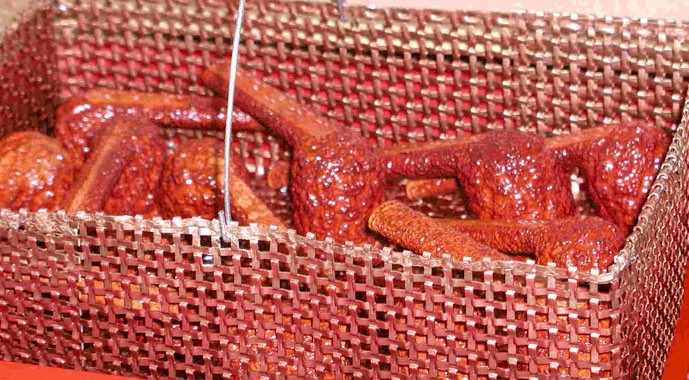

In carrying out my invention, I shape the pipe in the ordinary way. I then steep it for a suitable time in a mineral or vegetable oil. For instance, in the case of Algerian briar, a wood very suitable for the production of these new tobacco pipes, the article may be steeped for a long period say for several weeks, in olive oil. After lt has been removed from the oil, I subject the article to the action of heat. This process occupies a number of days, the oil exuded or coming to the surface being wiped off periodically. The result of the treatment is that the grain of the wood is hardened and stands out in relief to a certain degree, but the oil coming to the surface forms an impervious coating.

I (then) submit it to the action of the sand jet or sand blast, which removes the hardened coating of oil and also has the effect of cutting away the softer wood between the grain and leaving the harder portion -the hardness of which has been intensified by the process of steeping and heating- in very high relief. If the article is again steeped in oil, it will take up a further amount and the treatment by heat and the sand jet or sand blast may be repeated; and so on for as many times as may be required according to the extent to which it is desired to accentuate the grain or make it stand out in relief. The resulting article is extremely hard and constitutes an admirable tobacco pipe for the smoker.

The sandblasting techniques were not completely mastered by the Dunhill pipe makers in the beginning of the 1920’s. So the pipes were aggressively, deeply blasted through a “double blast” process. Because of the softness of the Algerian briar especially in the early years the shape of the pipes was often dramatically altered. Sometimes so much that the regular shape number no longer could be used. In the late 1920’s and 1930’s the blast was more controlled, but still deep and craggy. This style continued into the 1960’s and is now considered classic. Since the late 1960’s Algerian briar became unavailable for Dunhill thus much harder briar (Grecian) had to be used for the finish. The consequence of course was that the Shell blast became significantly more shallow. The stain of the Shell is black with an underlying layer of warm red. So especially older Shell pipes reveal a warm shade of red when you hold them in the light. However, I remember reading somewhere (can’t find it now, you always see this..) that Dunhill once decided to make the Shell finish all black. It was not appreciated by Dunhill fans..

I now have two Shell prince pipes, both from the patent era. And I LOVE them. The first is an army mount from 1927 or 1928. I saw this one on the English ebay; the mouthpiece was pretty oxidised, the white spot had turned black and the rim was a bit shaved off. It did have a “buy it now” price that was pretty low so without thinking any further I bought it. When I received the package and saw the pipe it looked better than on the pictures. I even could see the registration number on the stem. I send the pipe to the repairman and he did a wonderful job, it was good to go for years to come. Today this Shell prince is my benchmark pipe for latakia blends.

What I forgot with my first Shell I did do with my second: ask more about the pipe. My second Shell I recently bought (also on ebay) from a very nice British fellow named David. On the picture I saw a patent era Dunhill pipe from 1950 in pristine condition. Except for the tenon, which was cleanly broken. I took the gamble and made a bid which was, to my delight, the winning one. I send pictures of the broken tenon to the repairman and he just said: send it over. One and a half week later I received the pipe back and to my relief the repair was immaculately done. The original mouthpiece was saved, only the tenon had been replaced. I also saw a strange “C” stamp on the bottom that I did not not know of. Well, I know that a “C” stamp can stand for Churchwarden. But obviously this was no churchwarden. I kept on mailing with David (who in the past had a lot of informative talks with Richard Dunhill) and asked him if he knew anything more about the pipe. This was his answer:

What I forgot with my first Shell I did do with my second: ask more about the pipe. My second Shell I recently bought (also on ebay) from a very nice British fellow named David. On the picture I saw a patent era Dunhill pipe from 1950 in pristine condition. Except for the tenon, which was cleanly broken. I took the gamble and made a bid which was, to my delight, the winning one. I send pictures of the broken tenon to the repairman and he just said: send it over. One and a half week later I received the pipe back and to my relief the repair was immaculately done. The original mouthpiece was saved, only the tenon had been replaced. I also saw a strange “C” stamp on the bottom that I did not not know of. Well, I know that a “C” stamp can stand for Churchwarden. But obviously this was no churchwarden. I kept on mailing with David (who in the past had a lot of informative talks with Richard Dunhill) and asked him if he knew anything more about the pipe. This was his answer:

In answer to your question, I don’t, I’m sorry to say, have all the background to your pipe, but I am able to tell you that I purchased the pipe in Brighton (on the south coast of the UK) in about 1997. I purchased it from the estate sale of the original owner (whose name was not publicly declared at the time) and whom I understand received it from Alfred Dunhill Limited as a “gift” at some point in the early 1950’s. The pipe may have been given to him because of his association with the Dunhill business as a stockist, a valued supplier, a personal friend of the Dunhill family or perhaps even a favoured customer (actors, celebrities of the era and those notably in the public eye were actively courted and encouraged by Dunhill to be seen and photographed with ‘white spot’ pipes between their teeth in the 1940’s & 1950’s) Unfortunately, however, the exact provenance of your pipe we shall never know for sure.

In answer to your question, I don’t, I’m sorry to say, have all the background to your pipe, but I am able to tell you that I purchased the pipe in Brighton (on the south coast of the UK) in about 1997. I purchased it from the estate sale of the original owner (whose name was not publicly declared at the time) and whom I understand received it from Alfred Dunhill Limited as a “gift” at some point in the early 1950’s. The pipe may have been given to him because of his association with the Dunhill business as a stockist, a valued supplier, a personal friend of the Dunhill family or perhaps even a favoured customer (actors, celebrities of the era and those notably in the public eye were actively courted and encouraged by Dunhill to be seen and photographed with ‘white spot’ pipes between their teeth in the 1940’s & 1950’s) Unfortunately, however, the exact provenance of your pipe we shall never know for sure.

On the subject of the ‘C’ stamp, the reference you found is quite interesting as it depends on where and how the ‘C’ is used on a Dunhill product. For instance, it may indeed indicate ‘Churchwarden’ if aligned with the ‘style’ stamp, or a large capacity one-off bowl if used after the letters OD on a Dunhill ‘special’ (ODA’s & ODB’s being slightly smaller)… It was even used on top grade straight grain or ‘Dead Root’ pipes at one time to indicate the degree of quality e.g. DRA, then a DRB, DRC etc.. (I’ll stop now!!) – there are so many different subtleties in the stamping. Incidentally, the ‘C’ for complimentary was also used on other products as I had an early Dunhill lighter that had it over-stamped on the base and which I knew had been a retirement gift.

Pipes, such as yours and that are marked with a ‘C’ were deliberately undated (as there was no need to identify the start of the one-year guarantee period) and were stamped with the ‘C’ to show that they were given free of charge to their original owners. Most of the pipes specifically made for members of the British Royal Family were also, I understand, marked with the ‘with compliments’ ‘C’ stamp. That said, don’t get too excited… King George V, his son The Duke of Windsor and his successor, King George the VI, were famously known for ignoring the ‘royal drawer’ preferring instead, to select pipes for themselves from Dunhill’s standard, year-dated stock as they liked to ‘browse’ through the choice and extensive range on offer to all who visited the Dunhill shop in London.

I love information like this, for me it makes the pipe and history come alive. So I hope to stumble upon many more old Shell briar princes, for a good price of course. After all, I’m Dutch.