I was introduced to the wondrous world of snuff tobacco by Rob during the last Zutphen meeting. There I had some Pöschl Gletscherprise and I actually quite liked it. Some weeks later I went to a local tobacconist and bought all the snuff tobaccos he had (sadly not much..). Being a cheap Dutchman I must say, snuff taking is a lot easier for the wallet as pipe smoking! I started using it on a regular basis, for example at the office. Because of my stomach problems I unfortunately can’t really handle coffee any more and a sniff provides just the kick I need. In the time that followed I purchased more grinded tobacco products from another snuff snorting nation, England, and discovered to my amazement that snuff is still being made here in The Netherlands! But first some history and please remember, I am leaning here very, very heavily on Wikipedia.

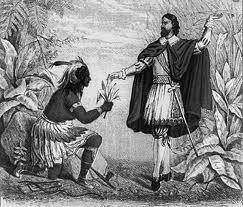

Native people from Brazil were the first that grounded tobacco to snuff. They would grind the tobacco leaves using a mortar and pestle made from rosewood, so the tobacco also got that delicate aroma. The resulting snuff was then stored airtight in ornate bone bottles or tubes to preserve its flavour for later consumption. Snuff-taking by the Taino and Carib people of the Lesser Antilles was seen by Ramón Pané, a Franciscan monk, on the second voyage to the New World by Colombus in 1493. Friar Pané’s return to Spain with snuff signalled its arrival in Europe.

In the early 16th century, the Spanish Casa de Contratación (House of Trade) was established. It held a trade monopoly in the first manufacturing industries of snuff in the grand city of Seville, which became Europe’s first manufacturing and development centre for snuff. The Spanish called snuff “polvo” or “rapé”. At first there were independent production mills were scattered throughout the city but were eventually concentrated in one place for health reasons and to facilitate state control of the activities. Seville’s (and Spain’s) first tobacco factory was in the Plaza de San Pedro in the heart of the medieval city. In 1725 it was decided to build a large and grand industrial building outside the city walls. And so the mighty Royal Tobacco Factory (Real Fábrica de Tabacos) was built. It became Europe’s first industrial tobacco factory and Spain’s second largest building at the time. At first snuff was produced and tobacco was auctioned. Later the famous “cigarreras” got to work there and more emphasis was put on cigars. For more info about tobacco in Seville and the Real Fábrica de Tabacos please read my 2 blogposts “Springtime in Seville” part 1 and part 2.

In 1561 the French ambassador in Lisbon, Jean Nicot, introduced snuff to the Royal Court of Catherine de’ Medici to treat her persistent headaches. She was so impressed with its relieving abilities that she promptly declared the tobacco would henceforth be named: Herba Regina (Queens’ Herb). Her royal seal of approval would help popularise snuff among the French nobility. In 1611 commercially manufactured snuff made its way to North America. John Rolfe, the husband of Pocahontas, introduced a sweeter Virginia variety which was also used for the production of snuff (also see my blogpost “Voluptuous Virginia“). Though most of the colonists in America never fully accepted the English style of snuff use (they preferred chewing or dipping tobacco), American aristocrats used the product. Snuff use in England increased in popularity after the Great Plague of London because people believed snuff had valuable antiseptic properties, which boosted its consumption. By 1650 snuff use had spread from France to England, Scotland, Ireland and throughout Europe, as well as Japan, China, and Africa.

In the 17th century some prominent opponents to snuff-taking arose. Pope Urban VIII banned the use of snuff in churches and threatened to excommunicate snuff-takers. In 1643 in Russia, Tsar Michael,who prohibited the sale of tobacco, instituted the punishment of removing the nose of those who used snuff, auwtsch! On the other hand, King Louis XIII of France was a devout snuff-taker. By the 18th century snuff had become the tobacco product of choice among the elite. Snuff use reached a peak in England during the reign of Queen Anne. It was during this time that England’s own production of ready-made snuff blends started. Prominent snuff users included: Pope Benedict XIII who reversed the smoking ban set by Pope Urban VIII. King George III‘s wife Queen Charlotte, referred to as “Snuffy Charlotte”, who had an entire room at Windsor Castle devoted to her snuff stock! And King George IV, who had his own special blends and hoarded a stockpile of snuff. Napoleon, Lord Nelson, the Duke of Wellington, Marie Antoinette, Alexander Pope, Samuel Johnson and Benjamin Disraeli all used snuff, as well as numerous other notable persons. The taking of snuff helped to distinguish the elite members of society from the common people, who generally smoked their tobacco.

Unfortunately the image of snuff as an aristocratic luxury resulted in the first U.S. federal tax on tobacco, created in 1794. In the late 1700’s, taking snuff nasally had fallen out of fashion in the United States. Despite this, during the 1800’s until the mid 1930’s, a communal snuff box was installed for members of the US Congress. Perhaps because a floral-scented snuff called “English Rose” is provided for members of the British House of Commons. This is due to smoking in the House being banned since 1693. A famous silver communal snuff box kept at the entrance of the House was destroyed in an air raid during WWII. A replacement was presented to the House by Winston Churchill. Sadly very few members are said to take snuff nowadays. In the 20th century the rise of cigarettes and cigars pushed back the use of snuff. However, in recent years, because of the ban on smoking in enclosed public places, the practice of snuff-taking is once again gaining popularity among men as well as women. This goes especially for youngsters from Morocco, Cape Verde and Germany.

Here in the Netherlands we were snorting away vast quantities of the finely grinded tobacco product by 1560. Besides, we made some of the best snuff available in the city of Amersfoort, it even was more famous than the stuff coming from Virginia! It was exported to most West- European countries, in which Germany, France en Italy were the biggest consumers. Snuff was also used in the mines in Limburg because underground the miners could not smoke because of the explosion danger. Of course snuff was also produced in other places like in for example Rotterdam. And, how very Dutch-like, it was made there in windmills. Now only 2 of those mills remain: “De Lelie” (The Lily) and “De Ster” (The Star). The great thing is, they are still in operation!

In 1740 “De Lelie” windmill was built, although its name back then was “De Ezel” (The Donkey). The first mention of “De Lelie” windmill (I guess they renamed it) was found in a deed of sale from 31 January 1777. Thijs van Zevenster and Jacob van de Werken then sell a piece of land with a windmill on it. After several owners the mill, together with a house and warehouse, was sold to Isaac Hioolen, master baker in 1803. Apparently business was going well for Isaac, because in 1829 he gave orders to constructed the corn-mill “De Nieuwe Star” (The New Star) at the Korte Kade in Kralingen. Sadly, when some years passed by, after being struck by lightning the mill burned down. At the site snuff and spices mill “De Stier” (The Bull), coming from Rijswijk (windmills are in essence big construction kits, dismantling and reconstructing is pretty easy), was rebuild in 1865. This mill was named “De Ster” after his predecessor.

The following Hioolen generations mainly focused on the production of snuff and spices. After the possessions of the Hioolens at the Kralingse Plas were expropriated because of the planting of the Kralingse Bos, the mills were rented to the foremen in 1916. When in 1962 “De Ster” burned down for the second time it brought an end to an industry that for over 160 years had existed at Kralingen. In 1970 the reconstruction was completed and since then the windmills were managed as a monument. In 1996 an enthusiastic group of volunteers began with making visible once again the old ways of snuff manufacturing to a wide audience. Interested folks, families, everyone can visit the windmills now and see how the snuff and spices are still made there.

So a select group of pipe-smokers of the Dutch/Belgian Pipe Smokers Forum stopped by the Kralingse (part of Rotterdam) snuffmills on a lovely Saturday. A bit too lovely because when we arrived the wings of mill were not turning. Oh well, we went inside and were warmly greeted by miller Jaap Bes. We sat down in a rather small room which served as reception chamber, canteen, museum and shop. Jaap is a retired teacher what was noticeable because with a natural calmness he stood before us and begun to tell about the history of the mill and his work. He also had prepared a sample of a new snuff with a mocha and coffee aroma but he was not really satisfied with it. Which shows his drive for perfection. I had a sniff of it and had a bit the idea that I was snorting grinded coffee.. Jaap also had an old book which practically fell apart with brown pages from 1862, with in it all kinds of snuff recipes! A lot of the current mill snuff offerings come from that book. Although often a bit changed. I mean, river-water as an ingredient? Not a good idea.. Soon we moved on to the spaces of the mill where the snuff actually is produced.

So a select group of pipe-smokers of the Dutch/Belgian Pipe Smokers Forum stopped by the Kralingse (part of Rotterdam) snuffmills on a lovely Saturday. A bit too lovely because when we arrived the wings of mill were not turning. Oh well, we went inside and were warmly greeted by miller Jaap Bes. We sat down in a rather small room which served as reception chamber, canteen, museum and shop. Jaap is a retired teacher what was noticeable because with a natural calmness he stood before us and begun to tell about the history of the mill and his work. He also had prepared a sample of a new snuff with a mocha and coffee aroma but he was not really satisfied with it. Which shows his drive for perfection. I had a sniff of it and had a bit the idea that I was snorting grinded coffee.. Jaap also had an old book which practically fell apart with brown pages from 1862, with in it all kinds of snuff recipes! A lot of the current mill snuff offerings come from that book. Although often a bit changed. I mean, river-water as an ingredient? Not a good idea.. Soon we moved on to the spaces of the mill where the snuff actually is produced.

At the windmills two kinds of the grinded tobacco product are made: rapé (grated) snuff and stem snuff. The latter is made from the stems and midribs of tobacco leaves and also whole leaves. Those are chopped directly in the casks in the mill. After that the snuff is sieved and grinded with the millstone, it is often mixed with flavourings such as rose oil, lavender oil and menthol. The mill only uses 2 species of tobacco: Virginia and Kentucky. 3 kinds of stem snuff are made: Virginia, fermented Virginia and latakia. Huh?? Latakia? Well, ehm, no. Despite in the old days the more mellow Syrian latakia was used for the making of snuff, the latakia of the mill is in fact Kentucky and Virginia. The Kentucky is fire-cured so the snuff gets a smoky aroma. First the raw leaves are sauced, then chopped, sieved, grinded and flavoured. Only the delicious Latakia Ao 1860 has no flavour. I also recommend the A/P and prize winning Chococrème-L- snuff. The Virginia snuff is the most easy to make. The raw leaves are not sauced but immediately chopped, sieved, grinded and flavoured. A good example is the Prins Regent snuff. With the fermented Virginia the raw leaves are sauced, chopped, sieved, grinded and flavoured. Then ammonium chloride and potash are added and the whole is put away for a while for further fermentation. After that you get a snuff like Son de Tonca No. 1.

To make the rapé, first the tobacco leaves are sauced. The composition of the sauce differs per snuff. Frequently used ingredients are for example kitchen salt, potash, rose water, liquorice water and juniper berries. After the saucing the tobacco leaves are stripped, weighed, wrapped in a linen cloth and entwined with a tight rope. This process is repeated after a week or two, then the rope and the cloth are removed. The carrot (such as the tobacco bundle is now called) is wrapped again, but now with a thin rope. That process is called “ficelleren”, I found no real English translation of it but “thin frapping” or “thin winding” comes near. Then the carrots go in storage so the fermentation process can take place. This can take months, sometimes years, but mostly about half a year. After the fermentation the carrots are finely grated or chopped. The name rapé snuff is derived from the French word for grating. Instead of grating by hand, carrots are also chopped in the mill. St. Omer No.1 is the name of the only rapé snuff that is sold.

It was fascinating to see Jaap preparing a carrot. All the handwork that comes with it.. Very labour-intensive! Suddenly outside the wind picked up and the mill sprang to life. Around us big and smaller wooden and metal parts grabbed together, moved, twisted and turned in a cacophony of movement and sound. Like being inside an old fashioned clock, just magical. When we went to the top of the mill I even got more respect for the people that once designed such a building. All that machinery that works from just a rotation of the blades, amazing! After the tour we of course could not resist buying vast quantities of the excellent quality snuff Jaap and the other volunteers made. The visit ended at neighbouring restaurant “De Tuin” where we had a pleasant High Tea. Other customers certainly must have thought we were “high”, seeing us snorting away our new acquisitions.

Now a bit about the technique of snuff taking. It is with snuff as it is with pipe tobacco, every snuff requires a sniffing technique of its own. In general, do not sniff too hard. It will get in your throat then which is not a nice experience, believe me! Just slowly but surely inhale, one nostril at the time. You want the snuff to be in the lower part of your nose, not fully up there, so you can taste it. With some snuffs you will have to sniff a bit harder, softer, longer or shorter. Experience is the key. Which way to take snuff depends for a great deal on how it is packaged. Here are some methods.

Now a bit about the technique of snuff taking. It is with snuff as it is with pipe tobacco, every snuff requires a sniffing technique of its own. In general, do not sniff too hard. It will get in your throat then which is not a nice experience, believe me! Just slowly but surely inhale, one nostril at the time. You want the snuff to be in the lower part of your nose, not fully up there, so you can taste it. With some snuffs you will have to sniff a bit harder, softer, longer or shorter. Experience is the key. Which way to take snuff depends for a great deal on how it is packaged. Here are some methods.

1. The anatomical snuffbox. When you stick out your thumb sidewards a small hole will appear in which you can put some snuff. I use this method with packages with a small hole.

1. The anatomical snuffbox. When you stick out your thumb sidewards a small hole will appear in which you can put some snuff. I use this method with packages with a small hole.

2. The three finger method. Put your index finger, middle finger and thumbs together. This creates a space in which you can put the snuff. I use this method with packages with a small hole.

2. The three finger method. Put your index finger, middle finger and thumbs together. This creates a space in which you can put the snuff. I use this method with packages with a small hole.

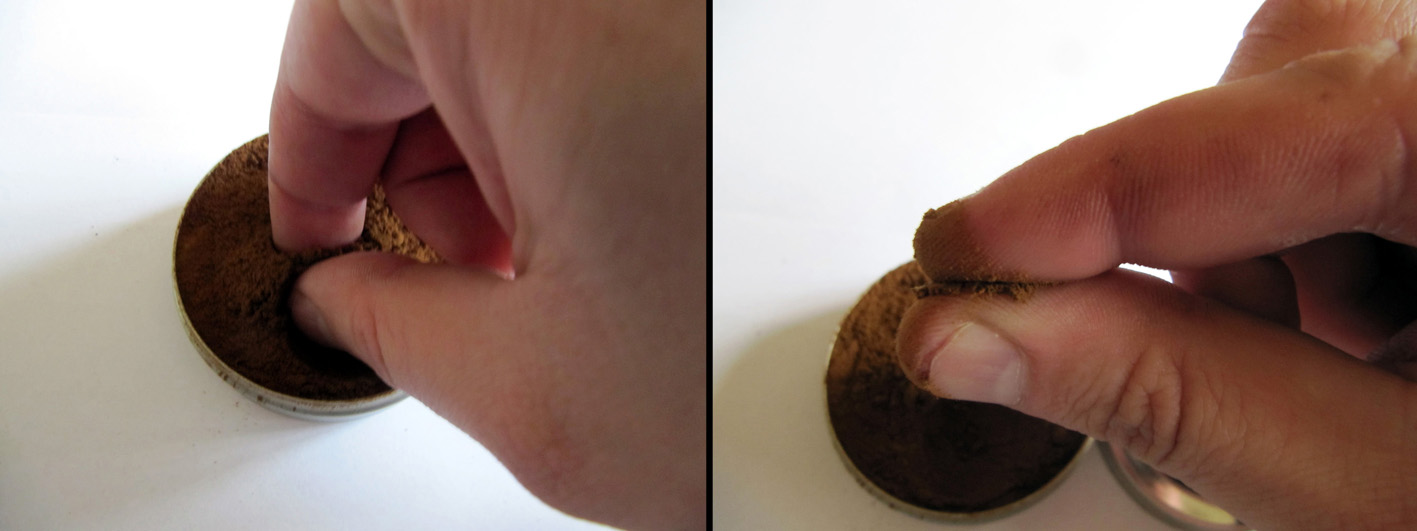

3. The “take a pinch method”. Take a pinch of snuff out of the tin between your index finger and thumb. I use this method with classic snuff tins.

3. The “take a pinch method”. Take a pinch of snuff out of the tin between your index finger and thumb. I use this method with classic snuff tins.

![]() 4. The “classic take a pinch method”. Take a pinch of snuff out of the tin between your index finger and thumb. Then move the index finger a bit back across the thumb. I use this method with classic snuff tins.

4. The “classic take a pinch method”. Take a pinch of snuff out of the tin between your index finger and thumb. Then move the index finger a bit back across the thumb. I use this method with classic snuff tins.

Here are some personal snuff recommendations:

– Bernard: Fichtennadel

– De Kralingse Snuifmolens: A/P, Chococrème-L-, Latakia A0 1860, Prins Regent, Son de Tonca No. 1, St. Omer No. 1

– Fribourg & Treyer: High Dry Toast

– McChrystal’s: Original & Genuine

– Pöschl: Gawith Apricot, Gletscherprise, Ozona

– Samuel Gawith: Kendal Brown Original

– Toque: USA Whisky & Honey

– Wilsons: SP Best, Grand Cairo

Here some informative links (if you know more links, let me know!):

– THE snuff forum with very friendly folks: Snuffhouse

– Modern Snuff

Some nice videos (in Dutch) from the snuffmils:

Last but not least a short clip of the immortal Laurel & Hardy

UPDATE 20-10-2016: Sadly De Kralingse Snuifmolens stopped selling snuff.. On Snuffhouse.com miller Jaap Bes explains it: Thanks for all your kind words. We are talking about to things that make me decide to stop selling snuff. First the mills are sold to a new owner without any consultations of the crew who runs the mills and this means we are not certain about the future. I intended to go on and look how things should go. Secondly I looked into the new EU regulations for tobacco: http://ec.europa.eu/health/tobacco/docs/dir_201440_nl.pdf Was it before this regulation became law in The Netherlands it was enough to fill out the forms about the products we make and the ingredients we use. Now we have to make determinations for example of the pH and % nicotin in every product.Also we have to give the exact tobacco composition of each product and also of all our used ingredients. All these demands can fulfilled by commercial companies, but as we are a non profit organisation run by volunteers with the aim to preserve historical production methods we can not. So I decided to stop selling snuff all together.