I always had a love for the Middle East; the pyramids and temples near Cairo, the ancient city of Damascus, the holy places in Jerusalem, the heart of the Ottoman empire Constantinople (Istanbul), mysterious Baghdad and the Muslim centre of Mecca. They all fascinate me to no extent. When I walked through the busy streets of the grand Khan el-Khalili bazaar in Cairo I knew I had to visit more places like that. Unfortunately, just as I was making plans to visit Damascus all hell broke loose with the still ongoing Syrian Civil War.

I always had a love for the Middle East; the pyramids and temples near Cairo, the ancient city of Damascus, the holy places in Jerusalem, the heart of the Ottoman empire Constantinople (Istanbul), mysterious Baghdad and the Muslim centre of Mecca. They all fascinate me to no extent. When I walked through the busy streets of the grand Khan el-Khalili bazaar in Cairo I knew I had to visit more places like that. Unfortunately, just as I was making plans to visit Damascus all hell broke loose with the still ongoing Syrian Civil War.

Talking about Syria, at the beginning of this year I received an e-mail from a Syrian-American named Kai. He had moved to Rotterdam last year for work (he is an architect) and he just got back to pipe smoking after taking a break for a while. Kai used to smoke Mac Baren HH Vintage Syrian in the USA and asked if he could get that blend in The Netherlands. I had to disappoint him but gave some tips where he would be able to buy it. We kept on mailing and I discovered that he was born in the Syrian port-city of Latakia. A word well known by us pipe-smokers because of the fire-cured dark leaf with the same name. Kai then was raised in Damascus until he moved to the USA just a few years before the civil war broke loose. Smoking the HH Vintage Syrian is his way to relate to his roots. Sadly his visa was not renewed by the Dutch government, which pissed me off pretty much, so now he is moving back to the States. But I promised Kai not to say anything about his situation in this blog. His dad always said, don’t get near two things in life: politics and drugs. A wise man. So Kai, this one is for you, enjoy the read.

According to an 18th century belief tobacco did not originate exclusively from the Americas but was also domestic in various parts of Asia and Africa. It was also believed that people in the Middle East used tobacco before my ancestors gazed upon the New World. However, since the 19th century the prevailing opinion has been that the Old World, including the Middle East, was introduced to tobacco by the early European discoverers.

According to an 18th century belief tobacco did not originate exclusively from the Americas but was also domestic in various parts of Asia and Africa. It was also believed that people in the Middle East used tobacco before my ancestors gazed upon the New World. However, since the 19th century the prevailing opinion has been that the Old World, including the Middle East, was introduced to tobacco by the early European discoverers.

Tobacco first arrived in the Ottoman Middle East at the end of the 16th century. Which is about 100 years after its introduction in Europe. At the beginning of the 17th century Portuguese and other European sailors, who travelled around the Indian Ocean within the Red Sea and Persian Gulf, introduced smoking to the Arabian Peninsula. Perhaps even as early as 1590 to Yemen and the Hijaz. 10 years earlier than tobacco’s introduction into Yemen it was brought to Constantinople by English sailors and traders who personally used tobacco.

Tobacco first arrived in the Ottoman Middle East at the end of the 16th century. Which is about 100 years after its introduction in Europe. At the beginning of the 17th century Portuguese and other European sailors, who travelled around the Indian Ocean within the Red Sea and Persian Gulf, introduced smoking to the Arabian Peninsula. Perhaps even as early as 1590 to Yemen and the Hijaz. 10 years earlier than tobacco’s introduction into Yemen it was brought to Constantinople by English sailors and traders who personally used tobacco.

At first tobacco mainly was the interest of physicians and appeared in medical manuals by the end of the 16th century. Its leaves were prescribed as a remedy for bites and burns. Soon after that, in the early years of the 17th century, tobacco also began to be smoked recreationally. In the first decades of the 17th century tobacco already was smoked openly in places where people gathered like markets and streets. These early smokers were probably townspeople who could have more readily afforded the expensive import from America and the Caribbean. A lot of those imported tobaccos came through the Syrian port of Latakia. However, by 1700 the Ottoman market was producing most of its own tobacco because, of course, regional merchants had noticed the demand. Local varieties allowed for the consumption of tobacco to become a pleasurable pastime for people from all levels of society (men AND women! Well, at least in the private sphere..) and the one constant was that it was certainly in high demand.

Later a number of regions within the empire became centres for tobacco production and distribution. Varieties of Indian, Syrian, Iraqi and Persian tobacco were imported and smoked in the Arabian towns. Local varieties of tobacco, known as tittun or dokhân were also cultivated and widely consumed within Arabia. Tobacco also was grown in Macedonia, Anatolia, northern Syria (particularly in the hills around the port of Latakia I mentioned before) and after some time in Lebanon and Palestine. Persian and Kurdish varieties, known locally as tunbak, were also prized but were mostly used in water pipes (hookah). This is correct because I asked Kai if he already smoked pipe in Syria. He answered that he did not smoke the tobacco-pipe, but made use of the water pipe. Only, he didn’t smoke the typical ultra-aromatic mu‘assel we associate with the hookah but used tunbak, which is a natural tobacco.

Later a number of regions within the empire became centres for tobacco production and distribution. Varieties of Indian, Syrian, Iraqi and Persian tobacco were imported and smoked in the Arabian towns. Local varieties of tobacco, known as tittun or dokhân were also cultivated and widely consumed within Arabia. Tobacco also was grown in Macedonia, Anatolia, northern Syria (particularly in the hills around the port of Latakia I mentioned before) and after some time in Lebanon and Palestine. Persian and Kurdish varieties, known locally as tunbak, were also prized but were mostly used in water pipes (hookah). This is correct because I asked Kai if he already smoked pipe in Syria. He answered that he did not smoke the tobacco-pipe, but made use of the water pipe. Only, he didn’t smoke the typical ultra-aromatic mu‘assel we associate with the hookah but used tunbak, which is a natural tobacco.

It was not easy for Middle Easterners to smoke tobacco for quite some time. That was made clear by the number of Islamic fatwas expressed by the Ottoman administration towards the lawfulness of smoking. This because tobacco was not known at the time of the Prophet, it is not named in the Qur’an. Which resulted in a debate over its legality to spread throughout the empire. The main question in debates was “if the consumption of tobacco was harmful to the user and his or her surroundings”. Islamic scholars interpreted general guidelines stated in the Qur’an or the hadith to support their arguments for or against its use. Soon after the rise in popularity of tobacco the religious authorities in Mecca grouped it with wine, opium and coffee. Thus issuing a fatwa banning it as an intoxicant.

It was not easy for Middle Easterners to smoke tobacco for quite some time. That was made clear by the number of Islamic fatwas expressed by the Ottoman administration towards the lawfulness of smoking. This because tobacco was not known at the time of the Prophet, it is not named in the Qur’an. Which resulted in a debate over its legality to spread throughout the empire. The main question in debates was “if the consumption of tobacco was harmful to the user and his or her surroundings”. Islamic scholars interpreted general guidelines stated in the Qur’an or the hadith to support their arguments for or against its use. Soon after the rise in popularity of tobacco the religious authorities in Mecca grouped it with wine, opium and coffee. Thus issuing a fatwa banning it as an intoxicant.

Not only was the debate over the consumption of tobacco religious, but also political. As early as 1610 an English traveller wrote about seeing “an unfortunate Turk riding about the streets of Constantinople….. Mounted backward on a donkey with a tobacco-pipe driven through the cartilage of his nose. Just for the crime of smoking”. I sometimes feel we are close to such a situation in our modern times.. Two years later, Sultan Ahmed I issued a temporary ban on smoking. In 1631, Murad IV began a campaign against the consumption of tobacco and outlawed its cultivation in the empire, but this failed. In 1633, after a devastating fire in Constantinople, Murad IV outright forbade tobacco consumption and inflicted severe punishment on smokers. During this time of smoking prohibition many people preferred to use crushed tobacco (snuff) to avoid being caught with a pipe. Murad IV also banned coffee and ordered the closure of coffee-houses, where both coffee and tobacco were consumed. What a horrible man..

Not only was the debate over the consumption of tobacco religious, but also political. As early as 1610 an English traveller wrote about seeing “an unfortunate Turk riding about the streets of Constantinople….. Mounted backward on a donkey with a tobacco-pipe driven through the cartilage of his nose. Just for the crime of smoking”. I sometimes feel we are close to such a situation in our modern times.. Two years later, Sultan Ahmed I issued a temporary ban on smoking. In 1631, Murad IV began a campaign against the consumption of tobacco and outlawed its cultivation in the empire, but this failed. In 1633, after a devastating fire in Constantinople, Murad IV outright forbade tobacco consumption and inflicted severe punishment on smokers. During this time of smoking prohibition many people preferred to use crushed tobacco (snuff) to avoid being caught with a pipe. Murad IV also banned coffee and ordered the closure of coffee-houses, where both coffee and tobacco were consumed. What a horrible man..

Fortunately the bans by Murad IV and others before him did not produce the desired results. Thus proving that coffee and tobacco consumption were already well rooted within the 17th century Middle East. In other words, smoking was not eradicated during these prohibitions. In 1646, during the reign of Ibrahim, the Turkish government issued a decree allowing for the consumption of tobacco. The religious legalization of smoking was granted in a fatwa issued in the early years of the 1720’s by Damascene Islamic scholar Abd al-Ghani al-Nabulsi. He wrote an essay entitled (I hope I type this correctly) “al Sulh bayna al-ikhwan fi hukm ibahat al-dukhkhan” which translates as “Peace Among Friends Concerning the Legalization of Smoking”. Al Nabulsi’s position on the consumption of tobacco was that smoking is like food. If it hurts stop it, if it does not, then why not smoke? Brilliant. The question regarding tobacco’s harmfulness remained a controversial issue for centuries to come. As it still is today. Nonetheless, it was not until the 18th century that tobacco consumption became a legitimate social pastime practice as was illustrated in many coffee-house illustrations of that time and later.

Fortunately the bans by Murad IV and others before him did not produce the desired results. Thus proving that coffee and tobacco consumption were already well rooted within the 17th century Middle East. In other words, smoking was not eradicated during these prohibitions. In 1646, during the reign of Ibrahim, the Turkish government issued a decree allowing for the consumption of tobacco. The religious legalization of smoking was granted in a fatwa issued in the early years of the 1720’s by Damascene Islamic scholar Abd al-Ghani al-Nabulsi. He wrote an essay entitled (I hope I type this correctly) “al Sulh bayna al-ikhwan fi hukm ibahat al-dukhkhan” which translates as “Peace Among Friends Concerning the Legalization of Smoking”. Al Nabulsi’s position on the consumption of tobacco was that smoking is like food. If it hurts stop it, if it does not, then why not smoke? Brilliant. The question regarding tobacco’s harmfulness remained a controversial issue for centuries to come. As it still is today. Nonetheless, it was not until the 18th century that tobacco consumption became a legitimate social pastime practice as was illustrated in many coffee-house illustrations of that time and later.

From the late 17th century onwards the tobacco pipe became a highly personalized possession in Arabia. With ornamented varieties coming from pipe-maker guilds in Turkey, England, France, Greece, Egypt, Palestine, and Lebanon. Probably every town of any size had at least one pipe-maker. Even potters in villages could turn out a few pipes from moulds brought from bigger cities. A lot of pipes were also produced in Mecca and Medina as smoking was popular in the heart of Arabia. Even the Sharif of Mecca engaged in tobacco consumption: “He sat upright on his divan, like an European, and smoked tobacco in a pipe like the “old Turks”. The simple earth-made bowl was set in a saucer before him, it’s white jasmine stem was almost a spear’s length.” Clay pipes were a preferable means for consuming tobacco. They were very portable and therefore more convenient to the highly mobile consumer (such as a pilgrim making the hajj). Furthermore clay tobacco pipes were readily available in any market and to customers from all levels of society.

From the late 17th century onwards the tobacco pipe became a highly personalized possession in Arabia. With ornamented varieties coming from pipe-maker guilds in Turkey, England, France, Greece, Egypt, Palestine, and Lebanon. Probably every town of any size had at least one pipe-maker. Even potters in villages could turn out a few pipes from moulds brought from bigger cities. A lot of pipes were also produced in Mecca and Medina as smoking was popular in the heart of Arabia. Even the Sharif of Mecca engaged in tobacco consumption: “He sat upright on his divan, like an European, and smoked tobacco in a pipe like the “old Turks”. The simple earth-made bowl was set in a saucer before him, it’s white jasmine stem was almost a spear’s length.” Clay pipes were a preferable means for consuming tobacco. They were very portable and therefore more convenient to the highly mobile consumer (such as a pilgrim making the hajj). Furthermore clay tobacco pipes were readily available in any market and to customers from all levels of society.

In the early 17th century two ways of smoking existed: “with water” or “dry”. But (of course) smoking tobacco through a dry pipe was superior to the water method. Which was done through the hookahs I mentioned earlier or narghiles, Middle Eastern innovations. The main device associated with tobacco consumption in the Arabian provinces was the oriental pipe, referred to in Turkish as the chibouk (Arabic: shibuk). The English-style kaolin pipes were likely to be more influential to styles in Istanbul, the imperial centre of the empire, where tobacco and the English pipes reached Turkey by the harbour. The 3-part chibouk arrived from North Africa in the Middle East and was readily adopted as the main instrument for smoking tobacco in the early 17th century. The chibouk consists of three elements: the head or bowl (Turkish: lüle), the stem and the mouthpiece. The bowls were made from a variety of materials including wood, stone, meerschaum or even metal. But the common material was clay. The stems were made of various woods or reeds and ranged in length from about 1 meter to 4 (!) meters. The mouthpieces were usually made of amber but could also be made of coral, gold and enamel. Precious stones could be added according to the taste and purse of the purchaser.

Climatic and cultural differences led to the development of two different types of pipes in Europe and the Ottoman Middle East. The hot weather in much of the Middle East created a preference for the inhalation of “cold smoke” while in the cooler weather of Europe smokers preferred “hot smoke”. Well, a moderate hot smoke of course. The technical solution to this issue of cooling the smoke within a dry pipe resulted in the 3-part style of the chibouk. For instance, the longer stem length allows the smoke to cool before it reaches the smoker. Wet silk was often applied to cover the stem to even increase its cooling capabilities. The longer stems, up to the 4 meters I mentioned before, were preferred in the hotter climes of the southern portions of the empire. Shorter stems, 20 centimetres to 1 meter, were used in the more northern, cooler climates. The varying lengths of stems are portrayed in numerous illustrations from the 18th and 19th centuries.

Climatic and cultural differences led to the development of two different types of pipes in Europe and the Ottoman Middle East. The hot weather in much of the Middle East created a preference for the inhalation of “cold smoke” while in the cooler weather of Europe smokers preferred “hot smoke”. Well, a moderate hot smoke of course. The technical solution to this issue of cooling the smoke within a dry pipe resulted in the 3-part style of the chibouk. For instance, the longer stem length allows the smoke to cool before it reaches the smoker. Wet silk was often applied to cover the stem to even increase its cooling capabilities. The longer stems, up to the 4 meters I mentioned before, were preferred in the hotter climes of the southern portions of the empire. Shorter stems, 20 centimetres to 1 meter, were used in the more northern, cooler climates. The varying lengths of stems are portrayed in numerous illustrations from the 18th and 19th centuries.

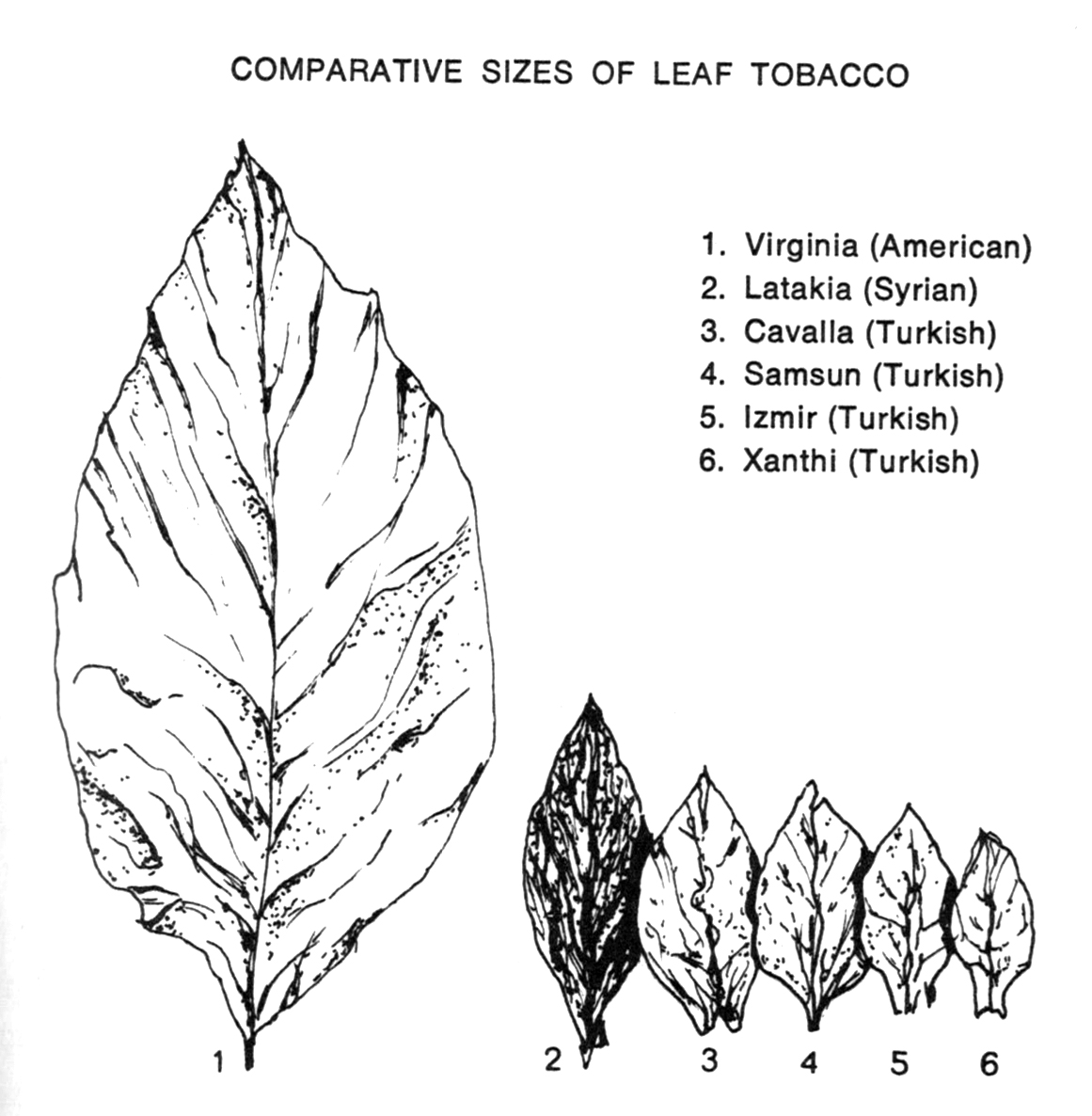

Today, tobacco is cultivated and cigarettes are manufactured in parts of the Middle East, North Africa and Muslim Asia. But only Turkey ranks among the world’s top 10 tobacco-producing countries. Though many reports claimed that the people of Persia and the Ottoman Empire consumed vast amounts of tobacco, actual consumption seems to have been less than in most parts of Europe. These days the tobacco consumption in Middle Eastern countries is only about one half of that in the West. In many countries most people used to smoke cheap, locally produced tobacco. Now more expensive import brands are popular almost everywhere. Either directly imported or manufactured under licence. Such a shame because it were the locally produced (oriental) tobacco gems that fascinated us pipe-smokers. As-salāmu ʿalaykum!

Today, tobacco is cultivated and cigarettes are manufactured in parts of the Middle East, North Africa and Muslim Asia. But only Turkey ranks among the world’s top 10 tobacco-producing countries. Though many reports claimed that the people of Persia and the Ottoman Empire consumed vast amounts of tobacco, actual consumption seems to have been less than in most parts of Europe. These days the tobacco consumption in Middle Eastern countries is only about one half of that in the West. In many countries most people used to smoke cheap, locally produced tobacco. Now more expensive import brands are popular almost everywhere. Either directly imported or manufactured under licence. Such a shame because it were the locally produced (oriental) tobacco gems that fascinated us pipe-smokers. As-salāmu ʿalaykum!